Hey Cinefiles!! Continue below to read an entry by Roger Kimmel Smith about the screening of Beverly of Graustark (1926) at the Wharton Studio Museum’s upcoming “Silent Movie Under the Stars” event happening on August 19th.

BEVERLY, MARION, AND SILENT FILM WORLD

by Roger Kimmel Smith

July 2023

I’m excited to attend the Wharton Studio Museum’s Silent Movie Under the Stars on August 19 at Taughannock Park — its thirteenth annual offering of this beautiful summer experience on Cayuga Lake. This year’s feature film, Beverly of Graustark (1926), starring Marion Davies, opens a viewfinder onto the captivating world of the silent film era, with some curious indirect connections to the Wharton brothers.

Davies starred in about thirty silent features between 1917 and 1928. I haven’t seen any of them — her work is rarely screened these days and almost none is available on home video — but from the couple of clips I’ve seen on YouTube, it’s easy to discern why historians and critics describe her as a very capable comedienne and a charming, energetic screen personality. Still, photos make clear hers was among the most exquisite female faces to appear on the silent screen.

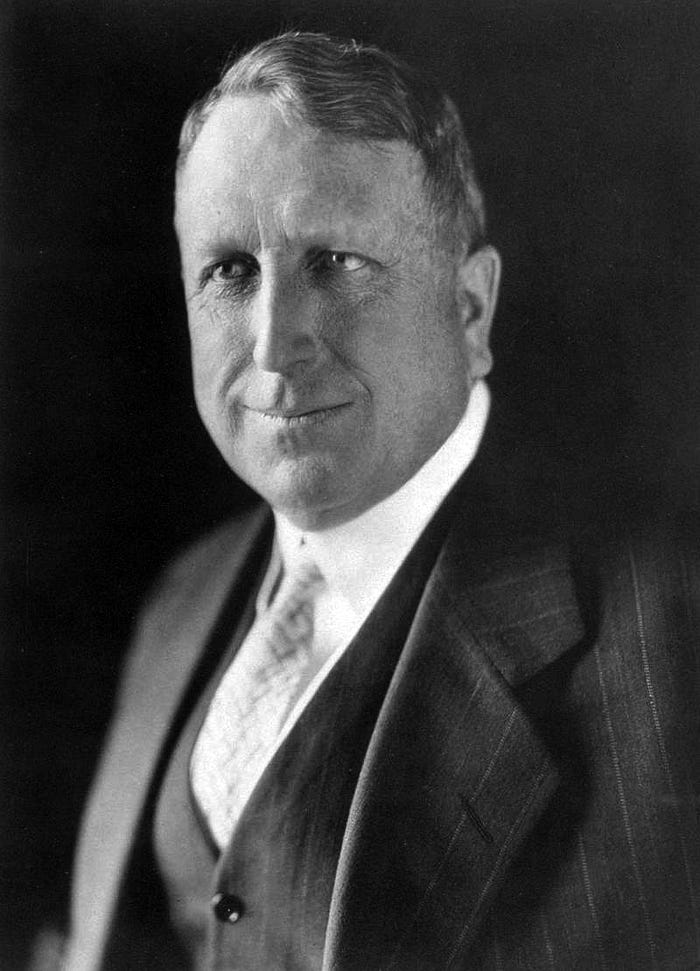

To make sense of Davies’ career, one has to grapple with the overweening influence of the powerful man she loved, the newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst. Here is where our story connects to the Wharton brothers, for Hearst was the Whartons’ most important financial backer during their years of high productivity in the 1910s.

FIRST/HEARST FLICKERS OF MULTIMEDIA

Hearst was the first true multimedia tycoon. He pioneered some of the business and marketing strategies that are now commonplace in the media industries. Hearst built a chain of dozens of daily papers that bore the recognizable stamp of his aggressive, populist style of journalism. From there he spread into magazines, buying Cosmopolitan in 1905, Good Housekeeping in 1911, and Harper’s Bazaar in 1913. The Hearst conglomerate owns all three of these venerable periodicals to this day.

Before 1910, Hearst had started syndicating material from his own papers, including Sunday comic strips, to outlets in fifty cities without their own Hearst publication. He founded two subsidiaries, International News Service and King Features Syndicate, to handle this lucrative trade.

The new, swiftly developing medium of moving pictures represented a logical extension of Hearst’s brand and properties. He began supplying news reels to theaters before the outbreak of World War I. To capitalize on the popularity of Krazy Kat and the other cartoons that appeared in his papers, he launched an animation studio in 1915. He also invested in the production of serialized short films, making a deal with the French company Pathé, which had gotten out to an early lead in the film business.

Hearst recognized the tremendous advantage his press empire could provide in publicizing the movies, especially in serial format; every week, his papers ran multiple items, photos, and script novelizations of the Hearst-Pathé offerings. The ballyhoo machine first fired up in support of The Perils of Pauline (1914) and its star, Pearl White. Pauline was neither the first nor the best movie serial of its time, but thanks to Hearst it far outpaced its competitors in name recognition, both then and a century later.

HEARST AND THE WHARTONS

Theodore Wharton helped bring White to the attention of Pauline’s director, Louis J. Gasnier, but was otherwise uninvolved in the production of the twenty-part serial. When Hearst decided to put White in another serial right away, however, Theo and his brother Leopold took over production. The Exploits of Elaine (1914, 14 parts), mounted and distributed on a bigger scale than Pauline — Pathé struck nearly five times the usual number of prints to ship to theaters — reportedly earned over one million dollars in film rentals.

The Whartons immediately cranked out multi-part sequels. The New Exploits of Elaine (1915, 10 parts) and The Romance of Elaine (1915, 12 parts) returned Arnold Daly and Creighton Hale to their co-starring roles opposite Pearl White, who as the intrepid Elaine Dodge proved to be a boldly independent female hero for the era of the “New Woman.” The Whartons shot The Romance of Elaine in Ithaca after completing the first two installments at Pathé’s Jersey City studio.

In partnership with Hearst, the Wharton brothers produced several more serials, including The New Adventures of J. Rufus Wallingford (1915) and the occult-tinged Mysteries of Myra (1916). In a blatant act of product placement, Theo and Leo brought Beatrice Fairfax (1916), the pen name for the Hearst-syndicated “Advice to the Lovelorn” column (which was first written by Marie Manning in 1898), to the screen as an adventurous reporter played by Grace Darling.

Tension between the Whartons and their wealthy patron became evident during the shooting of Patria (1917). This propagandistic “preparedness” serial transmitted Hearst’s unusual (to put it mildly) views on foreign policy in the lead-up to U.S. entry into the war in Europe — namely, that Japan, in concert with Mexico, was the true enemy power on which U.S. eyes should be fixed. Patria’s star was the well-known Broadway dancer Irene Castle (billed, most properly, as Mrs. Vernon Castle). After shooting the first ten out of fifteen episodes in Ithaca, the Whartons surrendered control to another production team in Los Angeles. By the spring of 1917 — before the U.S. Congress declared war on Germany — the Whartons had severed their ties with Hearst, announcing that they would become independent producers with their own distribution arm.

STAGE-DOOR JOHNNY AND THE GIRL ON THE MAGAZINE COVER

Meanwhile, Hearst had developed a new interest in the movies. That interest, to be specific, was in a Broadway chorus girl named Marion Cecilia Douras. Marion was born in Brooklyn in 1897 and grew up in an upper-middle-class family with three older sisters, two of whom preceded her into show business. The eldest, Irene, fourteen years her senior and nicknamed Reine, had taken Davies as her professional surname. Rose and Marion followed suit.

Both Hearst and Davies, for most of their lives, had reason to conceal the true facts concerning when and how they met. The historian David Nasaw, in his Hearst biography The Chief (2000), pinpoints the moment as the last few days of 1915. At that time, the 18-year-old Davies was appearing in the Irving Berlin musical Stop! Look! Listen!, which featured her, presciently, in a song called “The Girl on the Magazine Cover.” The Chief was a notorious “stage-door Johnny”: his wife, Millicent Willson Hearst, had been a teenage chorus girl herself when she met the young Will Hearst twenty years earlier.

By the middle of 1916, the fair face of Miss Davies was beginning to appear with some frequency in the dramatic pages of Hearst’s New York American, such as when she was cast in that year’s Ziegfeld Follies. The pair had become, so to speak, an item — though one the publisher strove valiantly to keep off the society pages.

Davies had great vivacity, a stunning, dainty face, and some dancing and comedic talent. She also had a persistent stammer that could easily have hindered her progression into speaking roles. It’s impossible to know how her career might have developed absent the increasingly ostentatious boosts her suitor gave to her public profile. It appears to be true, however, that Hearst had little or nothing to do with her first film appearance in a leading role. Runaway Romany (1917) was produced and directed by George Lederer, Reine Davies’ husband and Marion’s brother-in-law. After seeing it, Hearst offered his mistress a one-year film contract at five hundred dollars a week.

References in the trade press suggested that Hearst intended to frame his new star in the mold of Mary Pickford. Indeed, their first picture working together, Cecilia of the Pink Roses (1918, with Davies listed as producer), cast Davies in a Pickford-like role — eldest daughter in a poor family, forced by her mother’s death to care for her father and brother. Cecilia is consistent with Davies’ later roles in another way. Over the course of the film, her character is educated, travels abroad, and morphs into an elegant woman of the world, a stark change from how she is first presented.

DUAL MARIONS

As the Great War came to an end, Hearst decided to form his own film studio, which he named Cosmopolitan Productions — after the magazine, which he expected would supply material for scenarios. Early in 1919 he struck a distribution deal with Adolph Zukor of Paramount (or Famous Players-Lasky). He hired the screenwriter Frances Marion, who had scripted many Pickford pictures, to write roles for Davies. Over the coming years, he closely controlled every aspect of Davies’ career, determined not solely to make her a star of the first order but to ensure that every role she took presented her with class and dignity.

Hearst’s aesthetic preferences were decidedly conservative and old-fashioned. He did enjoy viewing Davies wearing frilly dresses in costume dramas. But my own view is that Hearst’s choices in his stewardship of Davies’ stardom were intermingled with the dicey ethics of their real-life romance. Because he could not live without her but refused to divorce Millicent, they both knew Davies, despite fame and wealth, would be denied a certain respectability in the eyes of society. This may be what drove him to protect the dignity of her on-screen image so fiercely.

To some extent, however, it seems that Hearst’s choice of material hindered the flourishing of her greatest strength as an actress — her vibrancy in light comedy. Between the weighty costumes, the sentimental roles in high-budget filmed spectacles, and the unrelenting overexposure she received in the Hearst media, she could easily have worn out her welcome with audiences. Instead, her popularity gradually rose.

Eventually, a way forward, or a workaround, emerged. Her pictures began consistently serving up Davies in multiple guises — variations on the rags-to-riches formula of Cecilia of the Pink Roses. In Adam and Eva (1923), it’s riches to rags. In Beauty’s Worth (1922), she blossoms from a primly homespun Quaker into a fashion plate. In Lights of Old Broadway (1925), she plays twins separated at birth. “Duality” roles — two Marions for the price of one — became her ticket, allowing her to express herself with comic zest while also appeasing the penchant of her lover/producer for dressing her up. Was one Marion Hearst’s and the other ours, the public’s, or is that too simplistic?

In her first big hit, When Knighthood Was in Flower (1922), her character poses as a male during a key adventure sequence. She would spend large portions of Little Old New York (1923) and Beverly of Graustark (1926) in male impersonation, to both comic and fashionable effect. She looks great in pants and slicked hair. (Parenthetically, it should be noted that the actor playing her romantic interest in the smash hit Little Old New York is named Harrison Ford.)

GRAUSTARKIAN COMPATRIOTS

All this background may afford us some basic literacy for decoding Beverly of Graustark. It is adapted from a novel published in 1904 by George Barr McCutcheon. McCutcheon, who was from Indiana and attended Purdue University, wrote at least five novels set in the fictional European principality of Graustark — enough that some people refer to the whole fictional-Euro-aristo-shtick as “Graustarkian” (an alternate is “Ruritarian,” from Anthony Hope’s novel The Prisoner of Zenda (1894)). McCutcheon also wrote a novel called Brewster’s Millions (1902), which was adapted for the screen nine different times between 1914 and 1985. The 1926 Beverly of Graustark is itself a remake; Biograph made a 57-minute version of it in 1914. Another Graustark adaptation was released in 1925, one year before Marion’s Beverly, starring Norma Talmadge from a Frances Marion script.

Davies has two important co-stars in Beverly. One is Antonio Moreno, who became famous for playing Latin lovers in Hollywood before Rudolph Valentino made his debut. In addition to Davies, during the 1920s Moreno co-starred in silent features opposite such actresses as Gloria Swanson (My American Wife, 1922), Colleen Moore (Look Your Best, 1923), Pola Negri (The Spanish Dancer, 1923), Greta Garbo (The Temptress, 1926), Dorothy Gish (Madame Pompadour, 1927), and Clara Bow (It, 1927).

Her other co-star, in the role of the Graustarkian Prince Oscar whom she impersonates in order to make sure he attains the throne, is the Irish actor Creighton Hale, whom Wharton followers will recognize from his role as Walter Jameson in the Exploits of Elaine serials. After appearing in a Wharton feature, Hazel Kirke (1916), and another Pearl White serial, The Iron Claw (1916), Hale played featured roles in at least twenty more silent films, such as D.W. Griffith’s Way Down East (1920), The Idol Dancer (1920), and Orphans of the Storm (1921), Ernst Lubitsch’s The Marriage Circle (1924), and the horror film The Cat and the Canary (1927). After the transition to sound, Hale’s career crumbled, but he hung around the studios playing uncredited bit parts in over one hundred talkies, including Becky Sharp (1935), The Maltese Falcon (1941), Casablanca (1942), and Sunset Boulevard (1950), where he played himself — one of the waxworks.

ROGER KIMMEL SMITH is a freelance wordsmith based in Ithaca. He hosts “Crazy Words, Crazy Tune” (“music and popular culture of the 1920s and 1930s in all genres and from around the world”), airing Fridays 12–2pm on WRFI Community Radio. He also produces and co-hosts the podcast “When Humanists Attack!!”

SOURCES:

Basinger, Jeanine. Silent Stars. New York: Knopf, 2000.

Gabrielle, Lara. Captain of Her Soul: The Life of Marion Davies. Oakland: University of California Press, 2022.

Lupack, Barbara Tepa. Silent Serial Sensations: The Wharton Brothers and the Magic of Early Cinema. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2020.

Nasaw, David. The Chief: The Life of William Randolph Hearst. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2000.